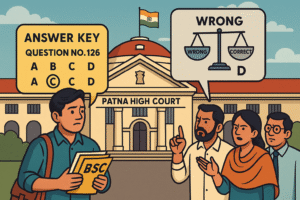

The Patna High Court has set aside a Magistrate’s order taking cognizance under Section 188 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) against a political functionary accused of violating permission conditions during an election meeting in Madhepura district. The Court, exercising its inherent jurisdiction under Section 482 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), held that prosecution for an offence under Section 188 IPC cannot proceed on a police report and requires a written complaint by the concerned public servant as mandated by Section 195(1)(a) CrPC. The petition was accordingly allowed, and the impugned cognizance order was quashed.

Simplified Explanation of the Judgment

This case arose from an election-time public meeting in April 2014 at a playground in Gamharia Block, Madhepura. The Sub-Divisional Officer had permitted a meeting for a limited time slot. According to the Block Development Officer (BDO), the event allegedly continued beyond the permitted time and a helicopter was landed despite restrictions, said to be a breach of the Model Code of Conduct. On the BDO’s written report, the police registered an FIR, investigated, and filed a charge-sheet. The Judicial Magistrate, 1st Class, Madhepura, then took cognizance—primarily for the offence under Section 188 IPC (disobedience to order duly promulgated by a public servant), and also noting Section 171C IPC in the course of argument. The accused approached the High Court under Section 482 CrPC seeking quashing of the cognizance order.

The crux of the High Court’s analysis lies in the special procedural safeguard built into Section 195(1)(a) of the CrPC. That provision creates a mandatory bar: no court can take cognizance of offences under Sections 172–188 IPC unless there is a “complaint in writing of the public servant concerned,” or of another public servant to whom the former is administratively subordinate. In simpler terms, when the allegation is that someone disobeyed an order of a public authority (e.g., timing limits for a meeting), the criminal court cannot proceed merely on a police FIR and charge-sheet. Instead, the concerned public official must file a formal written complaint directly before the Magistrate. Only then can cognizance be taken. The Court emphasized that this special procedure is an exception to the usual rule that a Magistrate can take cognizance upon a police report.

The Court further clarified the statutory definition of “complaint” in Section 2(d) CrPC. A “complaint” is an allegation made to a Magistrate with a view to his taking action. Crucially, a “police report” is expressly excluded from the definition of a complaint. The explanation to Section 2(d) only deems a police report to be a complaint in one narrow situation—where, after investigation, it discloses a non-cognizable offence. That deeming fiction does not apply to Section 188 IPC because Section 188 is cognizable in the First Schedule. Thus, even though Section 188 is cognizable, the specific bar under Section 195 overrides the general rule, and a police report cannot be the basis for cognizance.

The State argued that, because Section 188 IPC is cognizable, the police were duty-bound to register an FIR under the Constitution Bench ruling in Lalita Kumari v. State of U.P. The High Court disagreed that Lalita Kumari governs this situation. Citing the Supreme Court’s reasoning in Union of India v. Ashok Kumar Sharma (which dealt with a similar statutory bar under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act), the Court held that where a special statute—or a special provision like Section 195 CrPC—prescribes a particular mode for taking cognizance, the general mandate of automatic FIR registration and prosecution on police report does not control. Put differently, Lalita Kumari does not undo the explicit requirement of a written complaint by the public servant concerned when prosecuting an offence under Section 188 IPC.

Beyond the procedural bar, the Court also examined whether the basic ingredients of Section 188 IPC were even alleged. For Section 188 to apply, there must be: (a) an order duly promulgated by a lawfully empowered public servant; (b) knowledge of that order by the accused; (c) disobedience to that order; and (d) consequences such as obstruction to a person lawfully employed, danger to life/health/safety, or risk of riot/affray. The Court found that the written report did not identify the specific promulgated order that was allegedly disobeyed, nor did it set out the required harmful consequences or risk as contemplated by Section 188. Therefore, even on merits, the allegations failed to disclose a prima facie offence under Section 188 IPC.

Given these twin deficiencies—(1) the mandatory Section 195(1)(a) bar not being complied with, and (2) the failure to plead the necessary ingredients of Section 188—the Court concluded that continuing the prosecution would be an abuse of process. Invoking the well-known categories in State of Haryana v. Bhajan Lal, the Court held that the case fit at least two quashing categories: where the allegations even if taken at face value do not constitute an offence, and where there is an express legal bar to the institution and continuance of the proceedings. Consequently, the Court set aside the cognizance order insofar as it pertained to the petitioner.

In essence, the judgment reinforces that offences under Section 188 IPC are not to be prosecuted on auto-pilot via FIR and charge-sheet. The concerned public servant (whose order is claimed to have been disobeyed) must file a written complaint before the Magistrate. It also reminds prosecuting agencies to verify and plead the statutory ingredients of Section 188, including the particular order and the nature of the harmful effects or risks, before seeking to invoke the penal provision.

Significance or Implication of the Judgment (For general public or government)

• For citizens and political workers: The ruling clarifies that not every alleged breach of administrative directions during elections or public functions can be prosecuted through the police route. Where Section 188 IPC is invoked, a formal complaint by the concerned public servant is mandatory. This protects against hasty or vexatious prosecutions.

• For public officials: If a public servant believes there has been disobedience of a duly promulgated order, the correct legal path is to file a written complaint under Section 195(1)(a) CrPC before the Magistrate. A mere FIR to the police will not sustain cognizance for Section 188 IPC.

• For police and prosecutors: Even though Section 188 is cognizable in the Schedule, the special bar of Section 195(1)(a) must be respected. Before proceeding, ensure the presence of a proper complaint and that the complaint narrates the specific order, knowledge, disobedience, and the statutory consequences (obstruction/injury, danger to life/health/safety, or risk of riot/affray).

• For courts: The decision underscores early scrutiny at the cognizance stage to prevent unnecessary trials where Section 195(1)(a) is not complied with or where the Section 188 ingredients are not disclosed.

Legal Issue(s) Decided and the Court’s Decision with reasoning

• Whether cognizance under Section 188 IPC can be taken on a police report (charge-sheet) without a written complaint by the concerned public servant as required by Section 195(1)(a) CrPC.

— Decision: No. Section 195(1)(a) is a mandatory bar. Cognizance for offences under Sections 172–188 IPC can only be taken upon a written complaint by the concerned public servant or his administrative superior. A police report does not qualify as a “complaint” under Section 2(d) CrPC.

• Whether the facts alleged disclosed the essential ingredients of Section 188 IPC.

— Decision: No. The written report did not identify the specific order that was promulgated and allegedly disobeyed, nor did it allege consequences like obstruction to a person lawfully employed, danger to life/health/safety, or risk of riot/affray. Hence, no prima facie case under Section 188 IPC was made out.

• Applicability of Lalita Kumari (mandatory FIR for cognizable offences) where a special statutory bar (Section 195 CrPC) governs cognizance.

— Decision: Lalita Kumari does not override Section 195(1)(a). The special requirement of a written complaint by the concerned public servant continues to control the manner of taking cognizance under Section 188 IPC. The Court relied on the Supreme Court’s approach in Ashok Kumar Sharma to illustrate this principle.

• Whether the case falls within the quashing categories in Bhajan Lal.

— Decision: Yes. The allegations did not disclose an offence and there existed an express legal bar to prosecution, justifying quashing under Section 482 CrPC.

Judgments Referred by Parties

• Lalita Kumari v. State of U.P., (2014) 2 SCC 1

• State of U.P. v. Mata Bhikh, (1994) 4 SCC 95

• Daulat Ram v. State of Punjab, 1962 Supp (2) SCR 812

• C. Muniappan v. State of T.N., (2010) 9 SCC 567

• Apurva Ghiya v. State of Chhattisgarh, 2020 SCC OnLine Chh 454

• Union of India v. Ashok Kumar Sharma, (2021) 12 SCC 674

• State of Haryana v. Bhajan Lal, 1992 Supp (1) SCC 335

Judgments Relied Upon or Cited by Court

• State of U.P. v. Mata Bhikh, (1994) 4 SCC 95

• Daulat Ram v. State of Punjab, 1962 Supp (2) SCR 812

• C. Muniappan v. State of T.N., (2010) 9 SCC 567

• Union of India v. Ashok Kumar Sharma, (2021) 12 SCC 674

• State of Haryana v. Bhajan Lal, 1992 Supp (1) SCC 335

Case Title

Bijay Kumar @ Bijay Kumar Bimal v. State of Bihar & Anr.

Case Number

Criminal Miscellaneous No. 26029 of 2016; arising out of Gamhariya P.S. Case No. 66 of 2014 (District Madhepura).

Citation(s)

2025 (1) PLJR 738

Coram and Names of Judges

Hon’ble Mr. Justice Jitendra Kumar. (CAV; Pronounced on 07.01.2025)

Names of Advocates and who they appeared for

• For the petitioner: Mr. Shashi Bhushan Kumar Manglam, Advocate; Mr. Awnish Kumar, Advocate; Mr. Vikash Kumar Singh, Advocate.

• For the State: Mr. Upendra Kumar, APP.

Link to Judgment

NiMyNjAyOSMyMDE2IzEjTg==-TD69Yxbvd9M=

If you found this explanation helpful and wish to stay informed about how legal developments may affect your rights in Bihar, you may consider following Samvida Law Associates for more updates.