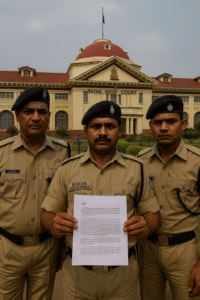

The Patna High Court has dismissed two petitions under Section 482 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) seeking to quash a 2015 cognizance order in a case arising from the disappearance and suspected killing of a teenager at a sand ghat in Bihta, Patna. The petitions challenged the Additional Chief Judicial Magistrate, Danapur’s order dated 07.10.2015 taking cognizance under Sections 302 and 201/34 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC). The High Court, per Hon’ble Mr. Justice Shailendra Singh, declined interference, noting that trial had already commenced and two prosecution witnesses had been examined. The Court treated the procedural lapse at the cognizance stage as, at best, an irregularity curable under Section 460 CrPC, and found sufficient material to proceed against the accused persons.

Simplified Explanation of the Judgment

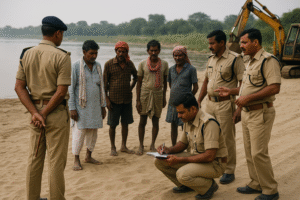

This case concerns an incident at a sand ghat on the Sone river in Bihta, Patna, where the informant’s minor son worked loading sand onto trucks with JCB machines. According to the defence version advanced before the High Court, the boy died in an accident: the JCB’s bucket allegedly hit his head, causing death. Out of fear, the operators and the munshi allegedly disposed of the body near the riverbank, after which floods could have swept the body away. The police later apprehended two JCB operators during investigation, recorded their statements, and initially proceeded under Sections 304A, 287, 281 and 120B IPC against three named persons, keeping investigation pending against others.

On the other side, the informant was not an eyewitness. He reached the sand ghat, did not find his son, noticed that the JCB machines were not operating, and suspected that the petitioner-accused and others had conspired to kill his son and had hidden the body. The complaint was thus largely based on suspicion, but the surrounding circumstances—non-functioning machines, absence of the body, and unsatisfactory explanations from those present—fueled the allegation of foul play.

During investigation, despite efforts including a dog squad search, the body could not be recovered, with the investigating officer opining that devastating flood waters of the Sone river may have swept it away. The informant also approached the High Court earlier through a habeas corpus petition (Cr.WJC No. 70/2014), pursuant to which even polygraph tests of the JCB operator and munshi were conducted. Nevertheless, the police case proceeded primarily on the accidental death theory with a chargesheet under Sections 304A, 287, 281, 120B IPC against some accused; investigation remained pending against the present petitioners when the Magistrate took cognizance under Sections 302 and 201/34 IPC.

The petitioners invoked the High Court’s inherent powers under Section 482 CrPC to quash the cognizance order. Their core grounds were: (i) cognizance was taken even though, for some of them, investigation was incomplete and no police report (chargesheet or final report) had been submitted; and (ii) the Magistrate did not proceed on the protest petition. For support, they relied on Abhinandan Jha v. Dinesh Mishra (AIR 1968 SC 117), particularly on the principle that while a Magistrate may disagree with a police report, the Magistrate cannot direct submission of a charge sheet and must follow the complaint procedure if treating a protest petition as a complaint.

The opposite party emphasized that the trial had already begun, charges had been framed, and two prosecution witnesses had deposed, arguing that quashing was unwarranted at such a stage. They also contended there was enough material in the case diary to justify cognizance for murder and disappearance of the body, even if some investigative steps were pending at the time of cognizance.

Assessing the record, the High Court identified key circumstances supporting the prosecution’s case: the suspicious conduct of those present at the ghat; the immediate disappearance of the body; and the absence of any clear sign of accident during investigation. Notably, no witness claimed to have seen either the alleged killing (as per the informant) or the accident (as per the defence). In the Court’s view, these circumstances justified the informant’s suspicion of a criminal offence and supported taking cognizance under Sections 302 and 201 IPC at least against one chargesheeted accused, while acknowledging a technical defect in summoning others during a still-pending investigation.

On the legal point, the Court clarified the contours of Section 190 CrPC: a Magistrate may take cognizance upon a complaint, a police report, information from any person other than a police officer, or upon the Magistrate’s own knowledge. Here, while a protest petition was on record, the Magistrate had not proceeded under that route, and more importantly, there was no police report regarding some petitioners when cognizance was taken against them. Thus, summoning them at that stage was “not in accordance with law.” However, the Court held that the error was an irregularity within Section 460 CrPC that does not vitiate subsequent proceedings, because sufficient material existed in the case diary to proceed against them and, by the time of the High Court’s review, trial had already moved forward.

Ultimately, considering the advanced stage of the trial and the presence of prima facie material, the High Court refused to set aside cognizance and dismissed both petitions.

Significance or Implication of the Judgment

For the general public and for investigating agencies, this decision underscores three practical points:

- Technical lapses at cognizance stage may not derail the trial if there is substantial material and proceedings have progressed. The Court treated the premature summoning of some accused (during an ongoing investigation) as an irregularity curable under Section 460 CrPC, not a fatal illegality, because the case diary still disclosed sufficient grounds to proceed and the trial had already begun.

- Magistrates’ power to take cognizance is broad, but its mode matters. Cognizance can be taken on various inputs (complaint, police report, information, or own knowledge). If the Magistrate relies on a protest petition, the complaint procedure must be followed. If cognizance is based on a police report, it should be against persons for whom the report/record justifies process; summoning others when investigation is incomplete can be questioned, though not always fatal if cured later.

- Timeliness matters once the trial starts. Where charges are framed and witnesses have been examined, superior courts are cautious about quashing proceedings unless there is a clear abuse of process. Here, the Court declined to interfere, highlighting judicial reluctance to halt trials mid-course absent compelling reasons.

Legal Issue(s) Decided and the Court’s Decision with reasoning

- Whether the Magistrate’s cognizance under Sections 302 and 201/34 IPC (on 07.10.2015) could be quashed under Section 482 CrPC when, for some accused, investigation was still pending and no police report had been filed.

• Decision: No. Although the Magistrate’s summoning of certain petitioners without a police report against them was “not in accordance with law,” it amounted to an irregularity under Section 460 CrPC that does not vitiate subsequent proceedings, especially where the case diary contained sufficient material and the trial had already progressed. - Whether the surrounding circumstances justified cognizance for murder and disappearance of evidence.

• Decision: Yes. The Court relied on circumstances: suspicious conduct at the sand ghat, absence of the body, non-working JCBs when the informant arrived, and lack of any eyewitness to either accident or killing—together justifying suspicion and cognizance, particularly against the chargesheeted accused, with adequate material also against others. - Whether the commencement of trial (charges framed; two witnesses examined) influenced the High Court’s discretion under Section 482 CrPC.

• Decision: Yes. The Court considered the advanced stage of proceedings and declined to quash, noting that interference would be unjustified in the circumstances.

Judgments Referred by Parties

- Abhinandan Jha & Ors. v. Dinesh Mishra, AIR 1968 SC 117. (Relied upon by petitioners to argue limits on Magistrate vis-à-vis police reports and the complaint route on protest petitions.)

- Nahar Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh & Anr., (2022) 5 SCC 295. (Cited by opposite party on Magistrate’s power to summon persons not sent up by police.)

- State of Gujarat v. Afroz Mohammed Hasanfatta, AIR 2019 SC 2499. (Cited by opposite party on sufficiency of grounds at issuance-of-process stage and non-requirement of detailed reasons.)

- Bhushan Kumar & Anr. v. State (NCT of Delhi) & Anr., (2012) 5 SCC 424. (Cited by opposite party; issuance of process under Section 204 CrPC does not require explicit reasons.)

Judgments Relied Upon or Cited by Court

- The Court noted Abhinandan Jha (AIR 1968 SC 117) but found it not directly applicable to the precise issue here (propriety of the cognizance order under review).

- The Court also observed that the other Supreme Court decisions cited by the opposite party were not directly relevant to the specific issue before it, though they elucidate general principles of cognizance and summoning.

Case Title

Criminal Miscellaneous Petitions under Section 482 CrPC: Ram Agya Singh @ Ram Adya Singh and Ors v. State of Bihar & Another

Case Number

Criminal Miscellaneous No. 53947 of 2015 (with Criminal Miscellaneous No. 55695 of 2015).

Citation(s)

2025 (1) PLJR 807

Coram and Names of Judges

Hon’ble Mr. Justice Shailendra Singh.

Names of Advocates and who they appeared for

- For the petitioners: Mr. Sanjay Kumar, Advocate (in both petitions).

- For the State: Mr. Binod Kumar, APP (Cr. Misc. No. 53947/2015); Mr. Ram Sumiran Roy, APP (Cr. Misc. No. 55695/2015).

- For Opposite Party No. 2: Mr. Rajendra Narain, Senior Advocate; Mr. Anil Kumar, Advocate (in both petitions).

Link to Judgment

NiM1Mzk0NyMyMDE1IzEjTg==-eVhpYNLGEks=

If you found this explanation helpful and wish to stay informed about how legal developments may affect your rights in Bihar, you may consider following Samvida Law Associates for more updates.