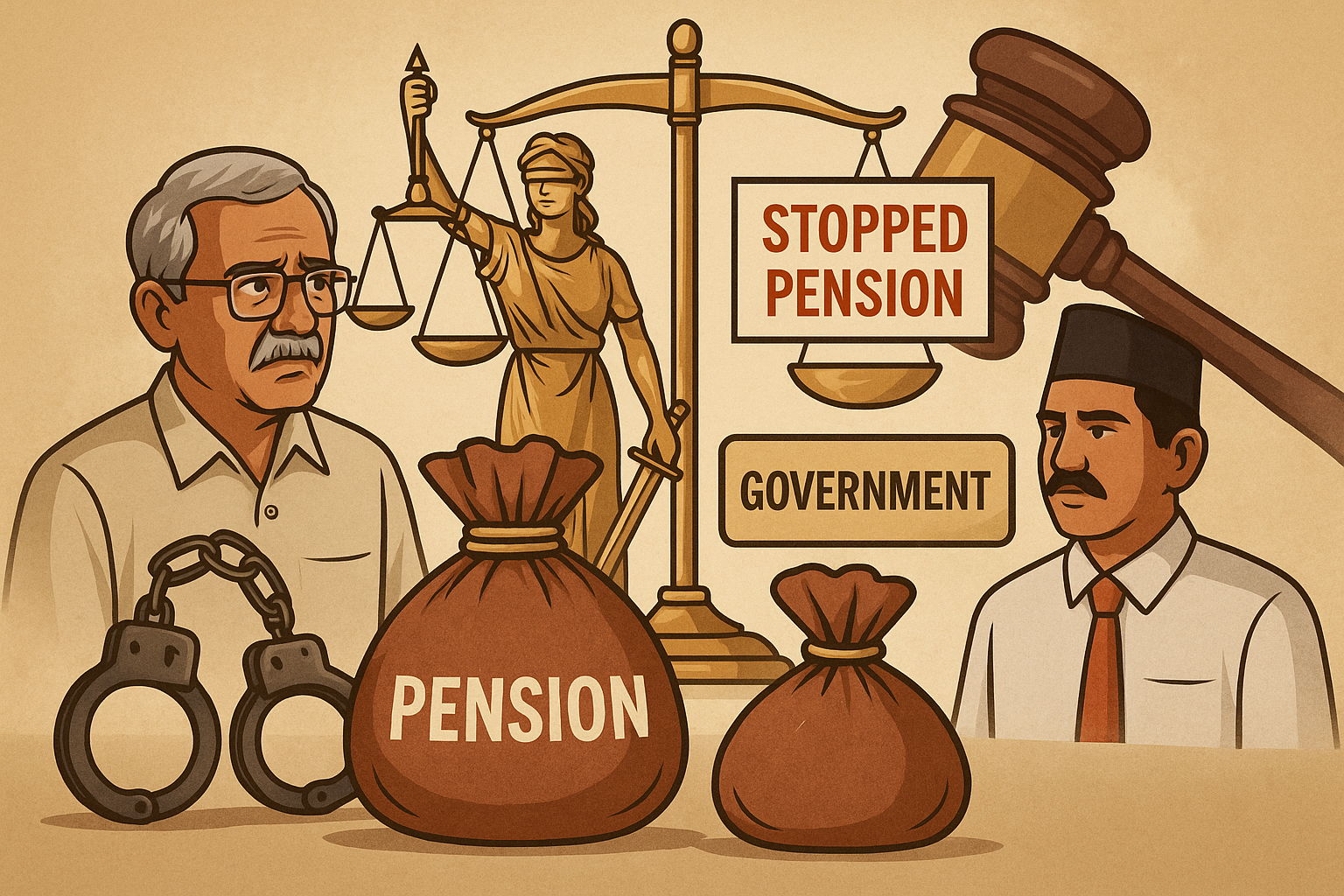

The Patna High Court has clarified how departments must proceed against retired government servants when criminal and disciplinary proceedings overlap. In a 2021 judgment, the Court set aside an order that had permanently forfeited 100% of a retired officer’s pension and directed that provisional pension be restored within six weeks, with fixation based on the last pay drawn at superannuation. The Court held that when the disciplinary authority itself accepts that the core bribery allegation is sub judice in a vigilance trial, it cannot, in the garb of a “note of disagreement,” introduce new charges or punish the employee beyond the scope of the framed articles of charge.

The petitioner, a former District Cooperative Officer, had originally approached the High Court seeking salary, regular pension, gratuity with interest, leave encashment, provident fund, and group insurance dues. Over time, the case evolved to challenge a later order that converted an ongoing departmental inquiry into a pension proceeding under Rule 43(B) of the Bihar Pension Rules and culminated in the drastic penalty of forfeiting the entire pension.

In the background lay a vigilance trap case registered in 2008, alleging the recovery of ₹11,000 in tainted currency notes and a demand for illegal gratification concerning a cooperative society position. A departmental proceeding had been initiated, then an order of dismissal from service was passed in 2014, which the High Court quashed in an earlier round of litigation, permitting the authorities to proceed afresh from the Rule 18 “second show-cause” stage of the Bihar CCA Rules. The petitioner superannuated in 2016 while those matters were still alive.

When the matter came up again, the department rescinded a 2018 “second show-cause,” issued a fresh one in July 2019, and — on the same date — decided to convert the disciplinary proceeding into a proceeding under Rule 43(B) of the Bihar Pension Rules, ultimately passing an order in August 2020 stopping 100% pension permanently and withholding a portion of gratuity.

The High Court’s core reasoning proceeds in three steps:

- The earlier writ order allowed the authorities to restart only from the Rule 18 stage under the Bihar CCA Rules. Even though the employee had retired, in view of the Court’s liberty, the authorities could (and should) have continued under the CCA Rules for the limited purpose of concluding the departmental proceeding. Unilaterally shifting to Rule 43(B) under the Pension Rules, without seeking modification of the earlier order, was unwarranted in the facts.

- On substance, the only charge actually framed concerned illegal gratification. The Department’s own record acknowledged that whether the seized money was “bribe money” was for the vigilance court to decide. Nevertheless, the disciplinary authority used the “note of disagreement” to go beyond the charge and to newly impute violations of Conduct Rules 17(5) and 17(6) (personal transactions without intimation), which were not part of the charge memo. This amounted to reframing charges at the penalty stage — impermissible under Rule 18.

- Since the inquiry officer had already opined that a conclusion on guilt should await the vigilance trial, and the disciplinary authority effectively conceded that the primary issue (whether money was bribe) was sub judice, there was no material foundation to disagree with the inquiry report and impose a major punishment like 100% pension forfeiture.

Accordingly, the Court quashed the August 10, 2020 pension-forfeiture order, directed restoration of provisional pension within six weeks, and clarified that pension fixation must reflect the last pay scale applicable to the officer’s post at the time of superannuation on 31.08.2016. Claims about arrears for the suspension period were left to be decided after the vigilance court’s judgment.

Simplified Explanation of the Judgment

This case concerns what a department may lawfully do after an employee retires while both a vigilance case and a departmental inquiry are pending. The employee (petitioner) had faced a vigilance trap allegation in 2008 involving ₹11,000. A departmental proceeding followed, ending in a 2014 dismissal order. In a prior writ proceeding, the High Court quashed that dismissal and specifically permitted the State to proceed “afresh” from the limited “Rule 18” stage of the Bihar CCA Rules. The employee then retired in 2016.

Instead of continuing strictly under Rule 18 as allowed by the Court, the department, in July 2019, converted the matter into a pension proceeding under Rule 43(B) of the Bihar Pension Rules and, in August 2020, imposed a major punishment: permanent stoppage of 100% pension and withholding part of gratuity. The State argued that this conversion was justified because the employee had retired. The petitioner argued that the department ignored the Court’s earlier directions and, moreover, could not punish him on the basis of materials (pre-trap and post-trap memoranda) whose evidentiary value would be tested in the vigilance trial.

The High Court agreed with the petitioner. First, it reasoned that the earlier liberty to proceed “from Rule 18” remained operative even after retirement—meaning the authorities could finish the departmental proceeding under CCA Rules for that limited purpose. If they wanted to switch to Pension Rules mid-stream, they should have sought modification of the Court’s order. They did not. Thus, in these facts, the conversion to Rule 43(B) was a misstep.

Second, the Court examined how the department used its “note of disagreement.” The sole framed charge concerned illegal gratification. The inquiry officer had said a final view should await the vigilance court’s decision. In its own note, the disciplinary authority admitted that whether the seized amount was bribe money was an issue for the vigilance court. Yet, the authority went further and faulted the employee for allegedly failing to inform about a personal transaction, invoking Conduct Rules 17(5) and 17(6)—a new line of misconduct not part of the charge. According to the High Court, this was an attempt to recast the charge at a late stage, which the law does not permit.

Third, once the department itself had acknowledged that the core bribery question was sub judice, there was no evidentiary basis to override the inquiry officer and impose a severe punishment like full pension forfeiture. The High Court emphasized that pre-trap and post-trap memoranda by themselves cannot conclusively establish guilt in the disciplinary proceeding while the criminal case is pending; more was required.

On relief, the Court:

- Set aside the order dated 10.08.2020 that had permanently stopped 100% pension.

- Directed restoration of provisional pension within six weeks.

- Ordered that pension be fixed on the basis of the last pay scale for the post held at superannuation (31.08.2016), allowing corrections in the last pay certificate if needed.

- Left the issue of suspension-period arrears to be decided after the vigilance case is concluded.

In short, the judgment protects retirees from punitive pension orders where the primary allegation is still under trial and the department tries to expand charges through a “disagreement note.” It reaffirms that departments must stay within the four corners of the framed charges and follow the exact procedural route the Court has allowed.

Significance or Implication of the Judgment

For the general public and government departments in Bihar, this judgment underscores four practical points:

- Retirement does not automatically give a free hand to switch every pending inquiry into a Rule 43(B) pension proceeding. If the High Court has directed continuation from a specific stage under the CCA Rules, departments must comply or seek modification.

- A “note of disagreement” is not a device to introduce new misconducts or expand the charge. It must respond to the inquiry report on the existing articles of charge and rely on evidence already on record.

- Where the core allegation is simultaneously the subject of a pending vigilance trial, departments should be slow to impose irreversible pension penalties based only on pre-trap/post-trap memoranda; such documents must withstand judicial testing first.

- Pension is a statutory right subject to lawful curtailment. Provisional pension functions as an important safeguard and cannot be withdrawn unless there is a solid, legally sustainable foundation. The Court’s direction to restore provisional pension within a time-bound schedule is a reminder of this.

Legal Issue(s) Decided and the Court’s Decision with reasoning

- Whether the department could convert a pending Rule 18 (CCA Rules) stage proceeding into a Rule 43(B) (Pension Rules) proceeding after the employee’s retirement despite the High Court’s earlier liberty limited to Rule 18.

Decision: In these facts, no. The Court had permitted continuation from Rule 18; switching tracks without modification of that order was improper. - Whether a disciplinary authority can, via a “note of disagreement,” go beyond the framed charges and construct new allegations (e.g., violations of Conduct Rule 17(5)/(6)) at the penalty stage.

Decision: No. The authority’s note attempted to introduce new misconducts beyond the charge memo, which is impermissible under Rule 18. - Whether 100% forfeiture of pension could be sustained when the primary bribery issue is acknowledged to be under trial before the vigilance court and the inquiry officer has advised awaiting that outcome.

Decision: No. Without an evidentiary basis to differ from the inquiry report, such a major penalty is unsustainable; pre-trap/post-trap memoranda alone cannot conclude guilt at this stage. - Reliefs: The 10.08.2020 order of pension forfeiture was set aside; provisional pension restored within six weeks; pension fixation to be on last pay at superannuation; arrears for suspension to await the vigilance court’s decision.

Judgments Referred by Parties (with citations)

- Ram Dayal Rai v. Jharkhand State Electricity Board, (2005) 3 SCC 501.

- Nandjee Mehta v. State of Bihar & Ors., 2017(1) PLJR 753.

- Dr. Ramavtar Prasad v. State of Bihar & Ors., 2008(4) PLJR 21.

- Jhakhari Ram v. State of Bihar & Ors., 2019(3) BLJ 233.

- Narmadeshwar Sharma v. State of Bihar & Ors., CWJC No. 8338/2009; LPA No. 131/2013 (unreported).

- Roop Singh Negi v. Punjab National Bank & Ors., (2009) 2 SCC 570. (Relied upon to argue that pre-trap/post-trap memoranda cannot by themselves be treated as conclusive evidence in departmental matters pending criminal trial.)

Judgments Relied Upon or Cited by Court (with citations)

- Earlier Patna High Court order in CWJC No. 19280 of 2015 (dated 10.04.2018) — quashed the earlier dismissal and permitted fresh action only from Rule 18 CCA stage; this direction framed the permissible scope of further departmental action.

Case Title

Suresh Prasad v. State of Bihar & Ors.

Case Number

Civil Writ Jurisdiction Case No. 12588 of 2019.

Citation(s)

2021(3) PLJR 23

Coram and Names of Judges

Hon’ble Mr. Justice Rajeev Ranjan Prasad.

Names of Advocates and who they appeared for

- For the petitioner: Mr. Akhilesh Dutta Verma, Advocate.

- For the respondents (State): Mr. Uday Shankar Saran Singh, GP-19.

Link to Judgment

MTUjMTI1ODgjMjAxOSMxI04=-hmbZ2qUv4Lo=

If you found this explanation helpful and wish to stay informed about how legal developments may affect your rights in Bihar, you may consider following Samvida Law Associates for more updates.