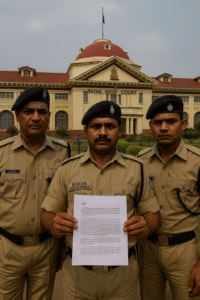

The Patna High Court set aside a blacklisting order issued by a state public-sector corporation and directed release of the petitioner’s earnest money deposit (EMD). The Court held that a clerical discrepancy in an experience certificate later clarified by the issuing authority could not, by itself, establish an intention to mislead or justify the severe civil consequence of blacklisting. The judgment was delivered on 25 March 2021 by Hon’ble Mr. Justice Anil Kumar Sinha.

- Simplified Explanation of the Judgment

This case arose from a large infrastructure tender concerning the design, construction, and operation of sewage treatment and network works in Munger, Bihar. The respondent public-sector corporation floated a Notice Inviting Tender in August 2019 for a 30 MLD sewage treatment plant with additional appurtenant works, a sewerage network of about 167.23 km, multiple pumping stations, and a multi-year O&M component. The petitioner (a company that had bid through a joint venture) submitted its bid on 7 January 2020 along with mandatory experience certificates and a bank guarantee of ₹3.4 crore as bid security.

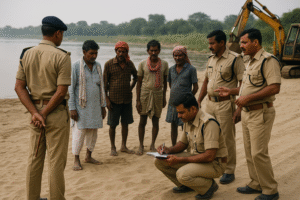

A few months later, the respondent corporation alleged that one of the uploaded experience certificates—relating to an underground drainage project in Okha, Gujarat—overstated the total pumping capacity. The certificate mentioned a total of 73.74 MLD, whereas on verification the issuing Executive Engineer of the Gujarat Water Supply and Sewerage Board confirmed that the completed works comprised 10 pumping stations totaling 32.51 MLD. On that basis, the respondent issued a show-cause notice dated 31 October 2020 proposing to blacklist the petitioner under the Bihar Contractor Registration Act, 2007.

Crucially, the issuing authority (the same Executive Engineer) later clarified—in writing—that the original certificate showed 73.74 MLD due to oversight and that subsequent changes during execution had reduced the number and capacity of pumping stations. The correction (32.51 MLD) had already been communicated to the respondent corporation in March 2020 during verification. The petitioner filed a detailed reply to the show-cause, enclosing this clarification and denying any intent to mislead.

Despite this, on 4 November 2020 the respondent blacklisted the petitioner for all departmental work and withheld the bid security. In the writ petition, the petitioner made it clear at the outset that it was not asking for consideration of its bid or for award of the contract; it limited its challenge to the blacklisting and to release of the earnest money.

Before the High Court, the petitioner argued that:

- The certificate in question was genuine; the discrepancy was a clerical/oversight error by the issuing authority, later corrected and informed to the respondent.

- Even without relying on that certificate, the bid already met the tender’s eligibility criteria through other experience documents, including a pumping station capacity and an STP of higher capacity than required.

- There was no motive to misrepresent because the corrected capacity still exceeded the minimum threshold laid down in the tender.

- Blacklisting, being a measure with grave civil consequences (often described as akin to “civil death” in contracting), requires clear evidence of intent or serious misconduct, which was absent.

The respondent corporation countered that the petitioner had signed and self-certified the documents uploaded with the bid. According to the respondent, the petitioner, being the contractor who had executed the Okha work, knew the actual capacity and therefore submitted the overstated certificate to gain an advantage.

After hearing both sides, the Court examined the record and focused on several undisputed features:

- The certificate containing the disputed figure (73.74 MLD) was issued in 2018—well before the 2019 tender—so it was not created for this bidding process.

- The issuing authority itself acknowledged the mistake and confirmed the correct figure (32.51 MLD) during the corporation’s verification in March 2020, and again in November 2020.

- Even the corrected capacity exceeded the tender’s minimum technical requirement, and the petitioner’s other experience certificates independently satisfied the eligibility criteria.

From these facts, the Court concluded that the petitioner did not intend to mislead and that the error was attributable to oversight by the author of the certificate. The Court emphasized that merely signing the uploaded documents could not, in the circumstances, be treated as proof of a deceptive intent. There was no finding that the certificate was forged; rather, the author expressly accepted the clerical mistake and set the record straight.

Given the gravity of blacklisting and its lasting consequences, the Court held that the impugned order could not stand. It quashed the blacklisting order dated 4 November 2020 and directed the respondent to release the earnest money of ₹3.4 crore if the bank guarantee had been invoked; if not invoked, the petitioner stood discharged from any obligation to renew it. The writ petition was accordingly allowed without costs.

In short, the Court drew a line between genuine, corrected clerical discrepancies and intentional misrepresentation. Where the tenderer’s eligibility was otherwise established and the issuing authority admitted its own error, imposing the extreme penalty of blacklisting was disproportionate and unsustainable.

- Significance or Implication of the Judgment (For general public or government)

This decision underscores that blacklisting is not a routine administrative response; it is an exceptional measure reserved for serious, proven misconduct. Government bodies must evaluate intent, materiality, and context before imposing such a penalty—especially where the contractor’s eligibility is otherwise satisfied and documentary discrepancies originate from the issuing authority. For the public and industry, the ruling is a reminder that:

- Clerical or verification-stage corrections—particularly when acknowledged by the issuing department—cannot automatically translate into permanent exclusion from public contracts.

- Procuring entities should adopt proportionate responses (such as seeking clarifications or rectifications) before resorting to punitive sanctions.

- Bidders must still exercise care while uploading and self-certifying documents, but they are not strictly liable for third-party clerical errors when promptly clarified.

- Legal Issue(s) Decided and the Court’s Decision with reasoning (Use bullet points)

- Whether a bidder can be blacklisted solely on the basis of a discrepancy in an experience certificate later clarified by the issuing authority as an oversight.

• Decision: No. Absent evidence of intent to mislead, a corrected clerical error cannot justify blacklisting. The Court found the petitioner had no motive to misrepresent and that other documents independently satisfied eligibility criteria. - Whether the bidder’s act of signing and uploading the documents establishes deceptive intent.

• Decision: No. Mere signature on uploaded documents, in the face of the issuing authority’s admitted error and subsequent correction, does not prove intent to mislead. - Appropriate relief when blacklisting is found unsustainable.

• Decision: The blacklisting order was quashed; the authority was directed to release the EMD if invoked, or treat the bidder as discharged from renewing the bank guarantee if not invoked.

- Judgments Referred by Parties (with citations) — Skip if none.

- Judgments Relied Upon or Cited by Court (with citations) — Skip if none.

- Case Title

Petitioner Company vs. State PSU (BUIDCo) (names withheld in narrative as per policy)

- Case Number

Civil Writ Jurisdiction Case No. 8973 of 2020.

- Citation(s)

2021(2) PLJR 219

- Coram and Names of Judges — Always prefix with Hon’ble

Hon’ble Mr. Justice Anil Kumar Sinha.

- Names of Advocates and who they appeared for

- For the petitioner: Senior Counsel assisted by advocates (names omitted in narrative as per policy).

- For the respondent corporation: Senior Counsel assisted by advocate(s).

- Link to Judgment

MTUjODk3MyMyMDIwIzkjTg==—ak1–F0fl9cHjLg=

If you found this explanation helpful and wish to stay informed about how legal developments may affect your rights in Bihar, you may consider following Samvida Law Associates for more updates.