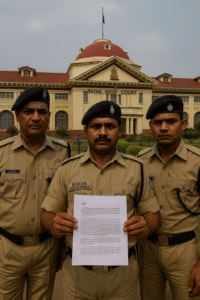

The Patna High Court in 2021 examined whether a municipal revenue-collection contract became impossible to perform because of the unprecedented COVID-19 lockdown. The petitioner had been awarded a one-year contract to collect parking charges within Nagar Panchayat, Maner for the financial year 2020–21. The work order issued on 18 March 2020 allowed collections from 1 April 2020 to 31 March 2021. Within days, however, a nationwide lockdown was declared on 24 March 2020, and movement of public transport was either stopped or severely restricted for months. As a result, there was no meaningful vehicular movement or parking revenue to collect.

The petitioner had already deposited a substantial amount as advance/security and later sought either an extension of six months (to compensate for the lost period) or a refund of the amount deposited. Repeated representations were made during August 2020 highlighting that transport services remained suspended and collections were practically impossible. Instead of granting an extension or refund, the municipal authority cancelled the allotment in October 2020 and asked for the balance of the bid amount, also pointing to an instance where a cheque presented by the petitioner bounced due to insufficiency of funds and to non-payment of stamp duty.

The High Court approached the dispute by focusing on the legal doctrine of “frustration of contract,” which is codified under Section 56 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872. The essence of the doctrine is that if, after a contract is made, an unforeseeable event beyond the control of the parties makes performance impossible or radically impracticable in light of the contract’s purpose, the contract becomes void to that extent. Crucially, “impossible” in Section 56 does not only mean literal impossibility; it also includes situations where performance becomes useless or impracticable from the perspective of the object the parties had in mind when they contracted.

Applying these principles, the Court noted that the work was to start on 1 April 2020 but the lockdown had already shut down normal movement (and particularly transport services) from 24 March 2020. This meant the parking sites were effectively closed or empty before the contracted period even began. The petitioner placed on record government notifications and orders showing extended restrictions on public movement and transport into mid/late 2020. The Court also recorded that the petitioner had, before the contract could meaningfully operate, made reasonable proposals—either extend the term by six months to neutralize the lockdown period or refund the deposit—yet the authority, acting mechanically, cancelled the allotment on 29 October 2020.

On these facts, the Court concluded that the contract had been frustrated by supervening circumstances beyond the petitioner’s control. The pandemic and lockdown were not contemplated at the time of bidding and could not have been reasonably foreseen. Because the very basis of the bargain—daily vehicle inflow enabling collection of parking charges—collapsed, insisting on performance or demanding full payment would be legally unsustainable.

The Court therefore set aside the cancellation letter and directed refund of the amount deposited by the petitioner within a stipulated period. In doing so, it rejected the authority’s argument that the petitioner had violated the terms and conditions, emphasizing that the core question was impossibility/impracticability of performance due to the lockdown, not any isolated transactional issue.

This decision is an important Bihar precedent on how municipal bodies and contractors should approach COVID-19-era contracts. It clarifies that where the central object of a contract is defeated by an unforeseeable, government-imposed lockdown, Section 56 can be invoked to prevent unjust enrichment and to ensure fairness. It also signals that public authorities must act with sensitivity and proportionality when faced with force-majeure-type events, rather than adopting a rigid “pay regardless” stance.

Significance or Implication of the Judgment

- For the general public and small contractors: The ruling reassures small businesses and individual contractors that courts will consider the real-world impact of lockdowns on government contracts. If the core purpose of a contract is defeated by circumstances like COVID-19 restrictions, courts may grant relief, including refund of deposits, rather than allowing authorities to forfeit amounts or demand full payment despite non-use.

- For municipal bodies and departments: The decision encourages authorities to evaluate pandemic-era contracts through the lens of Section 56. It underscores the need for policies that allow extension, remission, or refund in genuine cases instead of resorting to cancellation and recovery measures. Authorities should also consider incorporating clear, fair force majeure clauses and lock-in mechanisms to avoid litigation.

- For contract drafting and policy: The case highlights the importance of drafting robust force majeure clauses in public tenders, explicitly covering epidemics, lockdowns, and government restrictions. Such clauses should prescribe practical remedies—extensions, pro-rata fee adjustments, suspension periods, or termination with refund—so that parties have predictable outcomes when unforeseen events strike.

- For judicial consistency: By relying on the Supreme Court’s settled understanding of Section 56, the High Court maintains doctrinal consistency and provides a clear analytical path for similar disputes across Bihar where the pandemic rendered performance impracticable.

Legal Issue(s) Decided and the Court’s Decision with Reasoning

- Whether the parking-fee collection contract was frustrated due to the COVID-19 lockdown

• Decision: Yes. The nationwide lockdown and continued transport restrictions made performance impracticable; the contract’s core purpose—real-time collection from parked vehicles—was defeated.

• Reasoning: Section 56 of the Indian Contract Act covers supervening impossibility/impracticability. “Impossible” includes situations where performance is useless from the contract’s intended purpose. Pandemic lockdowns were unforeseen and directly prevented operation of parking sites. - Whether cancellation by the municipal authority and insistence on payment was justified

• Decision: No. The cancellation was quashed.

• Reasoning: The authority acted mechanically without appreciating the frustration of the contract. The petitioner had submitted reasonable representations seeking extension or refund; the authority failed to consider these in light of the lockdown’s legal effect on performance. - Whether the petitioner was entitled to refund of the deposit/advance

• Decision: Yes. The Court directed refund of the deposited amount within a fixed period.

• Reasoning: Once a contract is frustrated, insisting on consideration tied to non-performance is inequitable; refund prevents unjust enrichment and aligns with Section 56 consequences.

Judgments Referred by Parties (with citations)

- Delhi Development Authority v. Kenneth Builders & Developers Pvt. Ltd., (2016) 13 SCC 561 — cited to explain the ambit of Section 56 and how unforeseen governmental actions can frustrate a contract’s performance.

- Satyabrata Ghose v. Mugneeram Bangur & Co., AIR 1954 SC 44 — referred within the legal discussion on how “impossibility” in Section 56 also covers impracticability from the perspective of the contract’s object.

Judgments Relied Upon or Cited by Court (with citations)

- Delhi Development Authority v. Kenneth Builders & Developers Pvt. Ltd., (2016) 13 SCC 561 — relied on to restate the test for frustration under Section 56.

- Satyabrata Ghose v. Mugneeram Bangur & Co., AIR 1954 SC 44 — relied on for the seminal interpretation of “impossibility” as including impracticability and uselessness from the contract’s object.

Case Title

Petitioner v. Urban Development & Housing Department & Ors.

Case Number

CWJC No. 8307 of 2020

Citation(s)

2021(2) PLJR 226

Coram and Names of Judges — Always prefix with Hon’ble

Hon’ble Mr. Justice Anil Kumar Sinha

Names of Advocates and who they appeared for

- For the petitioner: Mr. Apurv Harsh, Advocate; Mr. Manu Tripurari, Advocate

- For respondent no. 2 (Executive Officer, Nagar Panchayat, Maner): Mr. Anil Kumar, Advocate

- For the State (A.C. to Standing Counsel-4): Mr. Upendra Pratap Singh

Link to Judgment

MTUjODMwNyMyMDIwIzkjTg==-B7kDmaX9LUM=

If you found this explanation helpful and wish to stay informed about how legal developments may affect your rights in Bihar, you may consider following Samvida Law Associates for more updates.