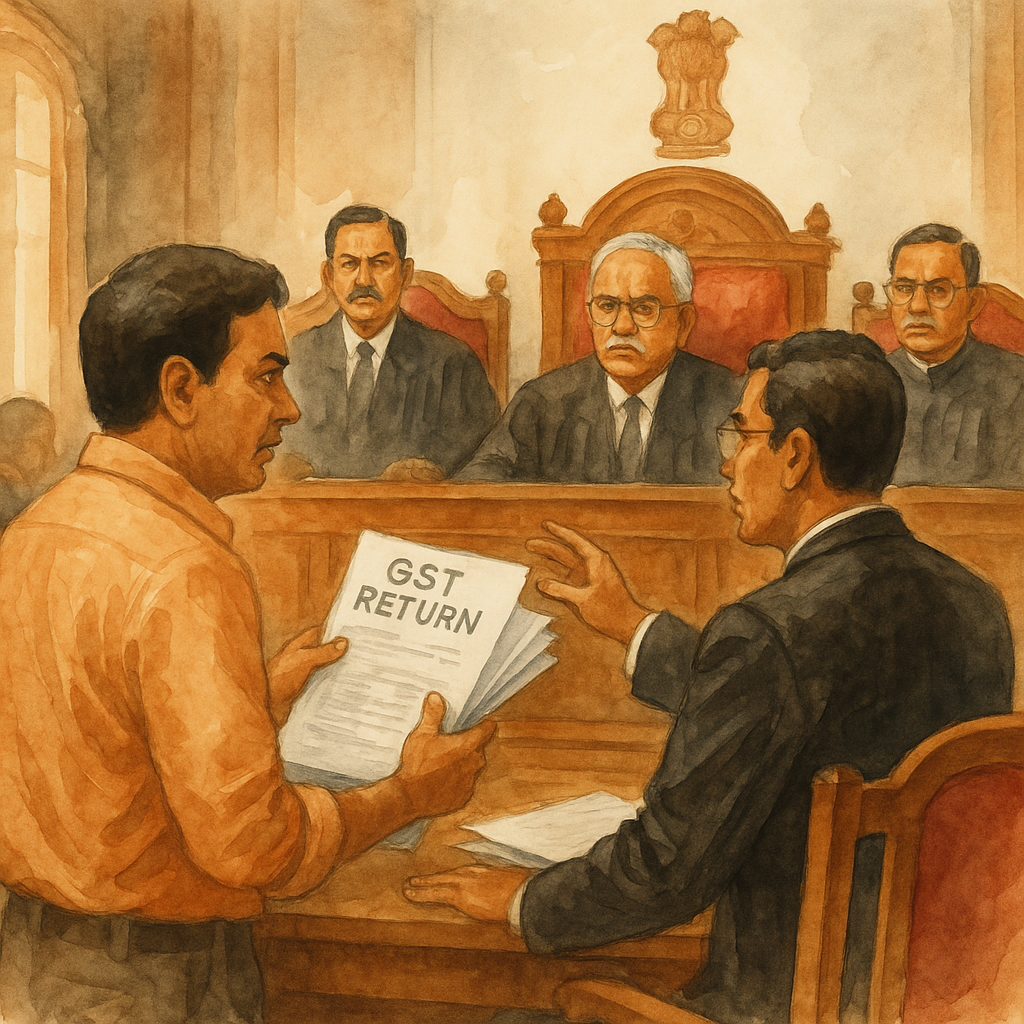

The Patna High Court has delivered an important judgment on the GST regime, upholding the constitutional validity of Section 16(4) of the Central and Bihar Goods and Services Tax Acts. In a batch of writ petitions led by CWJC No. 9108 of 2021, the Court rejected challenges mounted by various registered dealers who had claimed Input Tax Credit (ITC) after the statutory deadline. The petitions also questioned whether GSTR-3B is a valid “return” under Section 39 and attacked Rule 61(5) of the CGST Rules. All prayers were ultimately dismissed.

The lead facts were taken from one representative matter: the taxpayer filed GSTR-1 for 2018-19 but filed GSTR-3B for February and March 2019 only on 23.10.2019 and 07.11.2019. The State Tax Officer issued a Section 73 notice and then passed an order disallowing ITC solely because the returns were filed after the cut-off prescribed in Section 16(4). The appeal failed, and similar actions were taken in the connected cases.

The core constitutional attack was that Section 16(4)—which bars availing ITC after a fixed date (originally the due date for the September return of the following financial year; later amended to 30 November by Finance Act, 2022)—violates Articles 14, 19(1)(g) and 300-A, and is merely a procedural constraint that cannot override substantive entitlement under Sections 16(1) and 16(2). The petitioners also sought reading-down so that the embargo would apply only to invoices received after the end of the financial year.

After reviewing the statutory scheme of Section 16, the Bench held that ITC is a concession/benefit granted by statute, available strictly in the manner and within the time the statute prescribes. Sub-section (4) is not merely procedural; it is one of the mandatory conditions precedent to entitlement under Section 16(1). Therefore, non-compliance with the time limit disentitles a registered person from availing ITC.

The Court relied on Supreme Court precedents—particularly ALD Automotive Pvt. Ltd., which upheld a similar time-bar under the Tamil Nadu VAT Act—and Jayam & Company and Godrej & Boyce, to reiterate that tax credits are concessions that can be validly conditioned and time-limited by the legislature. Accordingly, Section 16(4) with its firm cut-off does not offend Articles 14, 19(1)(g) or 300-A.

Finally, the Court concluded that the batch of writ applications lacked merit and dismissed them, without costs.

Simplified Explanation of the Judgment

This decision clarifies a frequent point of dispute in GST: whether ITC can be claimed after the statutory deadline. The petitioners argued that because they had paid tax on their purchases (input tax), they had a vested, constitutionally protected “property” in that credit which should not be taken away for delay in return filing. They also maintained that Section 16(4) is a procedural rule that cannot defeat the “substantive” right to claim ITC under Sections 16(1) and 16(2). The Court disagreed.

First, the Court explained how Section 16 is structured. Section 16(1) grants entitlement to ITC, but expressly says it is “subject to” conditions and restrictions, and must be used as specified in Section 49. Section 16(2) adds further conditions through a non-obstante clause, and Section 16(3) adds another bar where depreciation on the tax component is claimed under the Income-tax Act. Against this design, Section 16(4) prescribes an outside time-limit to take ITC: after the stipulated date (originally the due date for the September return of the following year; from 01.10.2022, the legislature substituted “30th November”), ITC on invoices/debit notes of that year cannot be taken. The Court found no ambiguity here—these are substantive pre-conditions for entitlement, not mere procedure.

Secondly, the Court addressed the “property” and proportionality arguments. It reiterated the consistent view of the Supreme Court that ITC is not an indefeasible right; it is a statutory concession/benefit. As a result, the legislature may impose reasonable conditions including a time bar. The petitioners’ claim that Section 16(4) confiscates property under Article 300-A or imposes an unreasonable restriction on trade under Article 19(1)(g) was rejected. Fiscal legislation that uniformly applies to all registered persons is not, for that reason alone, violative of Article 19(1)(g).

Thirdly, on reading-down, the Court refused to re-write Section 16(4). When statutory language is clear, courts cannot “mend or bend” it to suit a perceived equitable result; either the provision stands or, if unconstitutional, it falls. Because the Court found Section 16(4) constitutional and unambiguous, there was no scope for reading-down.

Fourthly, the petitioners had also argued that GSTR-3B is not a “return” under Section 39 and that Rule 61(5) (which treats GSTR-3B as the Section 39 return) is ultra vires. The Court recorded these challenges but, having upheld Section 16(4) and found no infirmity in the statutory scheme, declined to accept the petitioners’ contentions. The batch was dismissed in toto.

For businesses in Bihar (and elsewhere), the practical takeaway is straightforward: claim ITC within the prescribed time. For invoices/debit notes of a given financial year, the outer limit to avail ITC is now 30th November of the following financial year (or the date of filing the annual return, whichever is earlier), for periods post-01.10.2022. Claims beyond this cut-off can be lawfully denied, even if tax on purchases was actually paid.

Significance or Implication of the Judgment (For general public or government)

- Certainty in compliance: The ruling cements that Section 16(4)’s time limit is a substantive condition. Taxpayers must complete return-filing and credit-availment on time; delays can cost the credit itself.

- Administrative uniformity: The Court emphasised uniform application of fiscal legislation, rejecting claims that the cut-off date is arbitrary or disproportionate. This supports consistent enforcement by both State and Central tax authorities.

- Reduced litigation: With the High Court aligning with Supreme Court principles on the nature of ITC as a concession, similar challenges are less likely to succeed, potentially reducing disputes over late-claimed ITC.

- Compliance planning: Taxpayers should tighten monthly return and reconciliation processes, especially vendor matching and invoice tracking, to ensure credits are availed within the statutory window.

Legal Issue(s) Decided and the Court’s Decision with reasoning

- Whether Section 16(4) of CGST/BGST is unconstitutional (Arts. 14, 19(1)(g), 300-A): No. ITC is a statutory concession; legislature may set a firm time bar. The provision applies uniformly and is neither arbitrary nor confiscatory.

- Whether Section 16(4) is merely procedural and can be ignored if Section 16(1)/(2) are satisfied: No. Sub-section (4) is a substantive, mandatory pre-condition to entitlement; failure to meet it disentitles the claim.

- Whether the Court should read down Section 16(4) to relax the cut-off: No. Language is clear; courts cannot re-write plain statutory provisions.

- Ancillary challenges (GSTR-3B not a Section 39 return; Rule 61(5) ultra vires): The Court noted these pleas but, in view of its conclusions on Section 16(4) and the statutory scheme, declined to accept them; the entire batch of petitions was dismissed.

Judgments Referred by Parties

- Modern Dental College and Research Centre v. State of M.P., (2016) 7 SCC 353 (proportionality) — relied upon by petitioners.

- K.T. Moopil Nair v. State of Kerala, AIR 1961 SC 552 — cited to argue against arbitrary taxation.

- Apfert Technologies Pvt. Ltd. v. Union of India (P&H), affirmed by Supreme Court — cited for “indefeasible right” argument (context noted by the Court).

- Vinoy Viswam v. Union of India — cited by petitioners in Article 14 challenge.

Judgments Relied Upon or Cited by Court

- ALD Automotive Pvt. Ltd. v. Commercial Tax Officer, (2019) 13 SCC 225 — upheld time-bar on ITC under TN-VAT; ITC is a concession.

- Jayam & Company v. Assistant Commissioner, (2016) 15 SCC 125 — ITC is not a right; conditions must be strictly fulfilled.

- Godrej & Boyce Mfg. Co. Pvt. Ltd. v. State of Maharashtra, (1992) 3 SCC 624 — followed in ALD Automotive.

- Jilubhai Nanbhai Khachar v. State of Gujarat, 1995 Supp (1) SCC 596 — on Article 300-A (Court’s discussion on property rights).

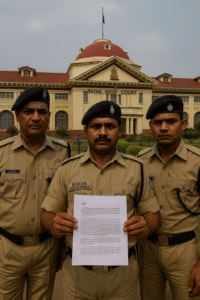

Case Title

Batch matters concerning Section 16(4) CGST/BGST (lead case: CWJC No. 9108 of 2021), Patna High Court.

Case Number

CWJC No. 9108 of 2021 with connected CWJCs (illustratively, 6397/2022, 7071/2022, 7222/2022, 7745/2021, 8569/2021, 9066/2021, 9566/2021, 9603/2021, 9733/2021, 9994/2021, 10044/2021, 16388/2022, 16396/2022, 16478/2022, 16659/2022, 17387/2022, 1753/2023, 2078/2023, 2187/2023, 7574/2023, 9927/2023, 9994/2023, etc.).

Coram and Names of Judges

Hon’ble Mr. Justice Chakradhari Sharan Singh and Hon’ble Mr. Justice Madhuresh Prasad (CAV Judgment dated 08-09-2023).

Names of Advocates and who they appeared for

- For petitioners (various matters across the batch): Senior Counsel and counsel including S.D. Sanjay, D.V. Pathy, Gautam Kumar Kejriwal, Sriram Krishna, Akshay Lal Pandit, Satish Chandra Jha-3, and others.

- For Union of India: Learned Additional Solicitor General.

- For State of Bihar: Learned Advocate General P.K. Shahi; Government Pleader-7 Vivek Prasad (among others).

Link to Judgment

MTUjMjg1NCMyMDIxIzEjTg==—am1–OyJ–am1–5LSOHQ=

If you found this explanation helpful and wish to stay informed about how legal developments may affect your rights in Bihar, you may consider following Samvida Law Associates for more updates.