The Patna High Court has allowed a criminal appeal and set aside a conviction under Section 376 IPC and Section 4 of the POCSO Act, emphasizing that criminal liability in a “statutory rape” case hinges on the prosecution’s ability to conclusively prove that the prosecutrix was a minor at the time of the incident. The Court held that approximate or uncorroborated opinions about age, and medical estimates unsupported by the examining radiologist’s testimony, are insufficient to sustain conviction.

In this appeal from a Special (POCSO) case, the trial court had convicted the appellant and imposed rigorous imprisonment of ten years along with fine; the sentences were directed to run concurrently. On appeal, the High Court scrutinised the entire record—FIR, the prosecutrix’s statement under Section 164 CrPC, deposition of witnesses, and the medical evidence—and concluded that the prosecution failed to discharge its primary burden of proving that the prosecutrix was below 18 years of age. Without reliable proof of minority, the relationship could not automatically be treated as rape under clause “sixthly” of Section 375 IPC, and the appellant was entitled to acquittal.

The Court noted important features that surfaced from the record: the prosecutrix and the appellant were in a physical relationship for a long period; termination of an earlier pregnancy occurred with knowledge of family members; the prosecutrix accompanied the appellant without raising alarm; and the alleged place of intercourse was the home of a relative who was not examined at trial. These facts, read together, suggested consent on the part of the prosecutrix, unless the prosecution could independently prove legal incapacity due to age. The High Court found that the age proof fell short of the stringent standard of “beyond reasonable doubt.”

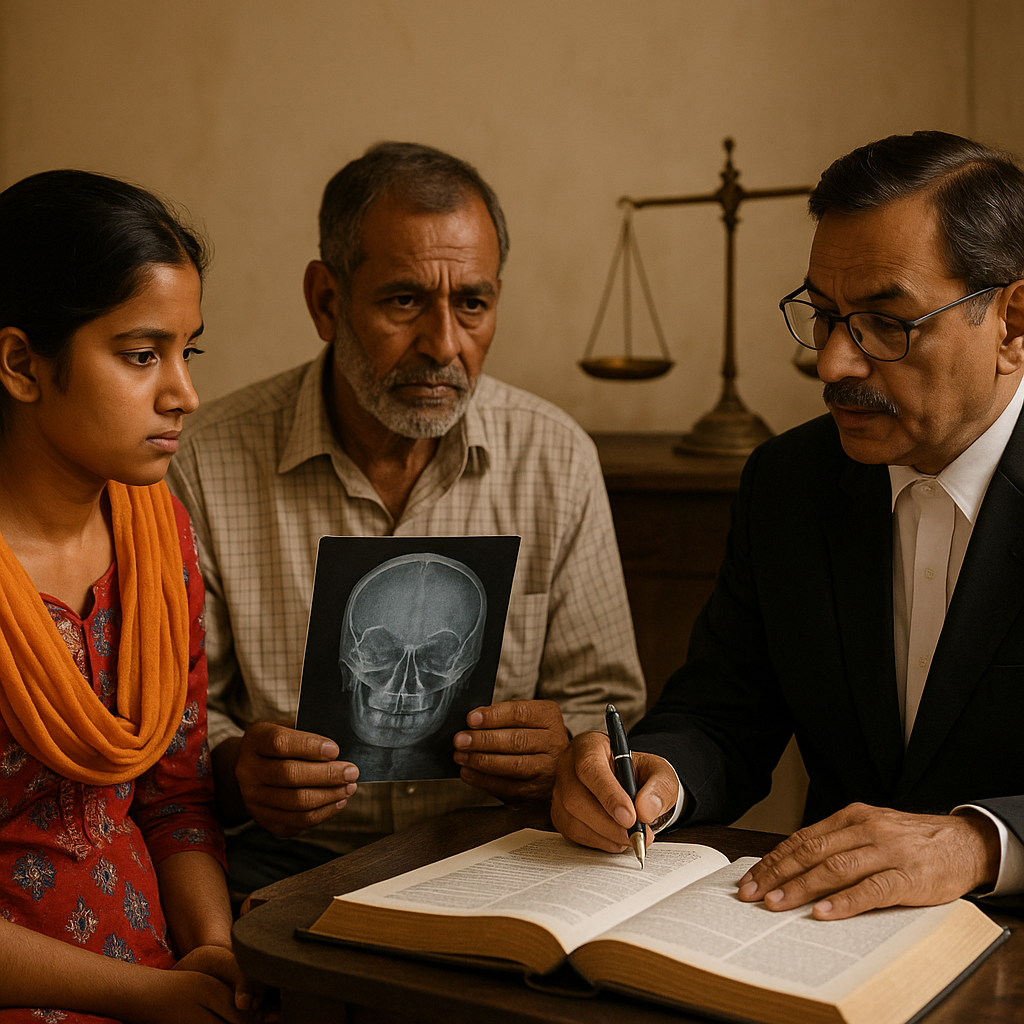

Significantly, the medical officer who testified stated that the age was “assessed between 16–17 years” on the basis of a radiological/ossification examination conducted by the radiology department; however, the radiologist who actually performed the test was not examined. The Court pointed out that such opinion became hearsay in the absence of the expert who conducted the age assessment. Moreover, no school records or birth certificates were produced, and even close relatives could only speak of an approximate age. The investigating officer also admitted that no school certificate was collected. In these circumstances, the Court applied settled principles from Supreme Court precedents, including Jarnail Singh (age determination to follow JJ Rules hierarchy and preference for school records) and Sunil v. State of Haryana (conviction cannot rest on approximate age), to hold that the statutory requirement of proving minority was not met.

Ultimately, the High Court set aside the conviction and ordered the appellant’s release. The judgment is a reminder to prosecutors and investigating agencies that, in POCSO/“statutory rape” prosecutions, proof of age is not a formality: it is a core ingredient that must be established by primary evidence such as school records, birth certificates, or the testimony of the competent expert who conducted the age determination. Where the prosecution relies on reverse burdens under special statutes, the State must still first establish foundational facts through trustworthy evidence.

Significance or Implication of the Judgment

This decision has practical implications for policing, prosecution, and trial courts in Bihar:

- Age proof is foundational in POCSO cases. The State must collect and present primary documents (school admission register, birth certificate) or ensure that the expert who conducted ossification/radiology tests testifies in court. Failure to do so risks acquittal even where other circumstances raise suspicion.

- Approximate or “best guess” ages are legally unsafe. Courts will not uphold convictions that rest only on family members’ estimates or on medical reports without the examining expert’s testimony.

- Investigating Officers must proactively trace and seize school records; omissions noted during cross-examination can be fatal.

- Trial courts must evaluate consent evidence separately from statutory incapacity. Where minority is not proved beyond reasonable doubt, consensual elements may defeat charges under Section 376 IPC read with POCSO.

For the public, the ruling underscores that POCSO is a stringent law designed to protect children, but convictions must rest on reliable, legally admissible proof that the person was indeed a “child” under law at the relevant time.

Legal Issue(s) Decided and the Court’s Decision with reasoning

- Whether the prosecution proved beyond reasonable doubt that the prosecutrix was below 18 years of age at the time of the alleged incidents so as to render her consent immaterial under clause “sixthly” of Section 375 IPC and Section 4 POCSO.

• Decision: No. The prosecution failed to produce school records or authentic birth documents; the radiologist who determined age was not examined; relatives only deposed approximate age. Hence, minority was not proved beyond reasonable doubt. - Whether, absent proof of minority, the relationship could be treated as rape under Section 376 IPC.

• Decision: No. On the evidence, the prosecutrix had been in a long-standing physical relationship with the appellant, had accompanied him without protest, and family members knew of prior pregnancy and its termination. These circumstances indicated consent; without proof of minority or vitiated consent (fraud, coercion, etc.), conviction could not stand. - Standard of proof and burden in criminal trials involving special statutes.

• Decision: Even where statutes cast a reverse burden at later stages, the prosecution must first establish foundational facts—here, age—through credible and admissible evidence. Non-cross-examination on age does not relieve the State of its burden to prove age beyond reasonable doubt.

Judgments Referred by Parties (with citations)

- Jarnail Singh v. State of Haryana, 2013 Cri. L.J. 3967 (on age determination and preference for school documents under JJ Rules).

- State of Madhya Pradesh v. Munna @ Shambhoo Nath, (2016) 1 SCC 696 (consensual relationship; prosecution failed to prove minority).

- Rajak Mohammad v. State of Himachal Pradesh, (2018) 9 SCC 248 (failure to prove minority leads to setting aside conviction).

Judgments Relied Upon or Cited by Court (with citations)

- Sunil v. State of Haryana, AIR 2010 SC 392 (conviction cannot be based on approximate age).

- Jarnail Singh v. State of Haryana, 2013 Cri. L.J. 3976 (age determination as per Rule 12 of JJ Rules; preference for school documents).

- State of Madhya Pradesh v. Munna @ Shambhoo Nath, (2016) 1 SCC 696 (approximate age insufficient; consensual elements relevant where minority not proved).

- Rajak Mohammad v. State of Himachal Pradesh, (2018) 9 SCC 248 (conviction set aside where minority not proved).

Case Title

Appellant v. State of Bihar.

Case Number

Criminal Appeal (SJ) No. 798 of 2017; arising out of Kotwali P.S. Case No. 489 of 2014, Patna.

Citation(s)

2021(2) PLJR 152

Coram and Names of Judges

Hon’ble Mr. Justice Birendra Kumar (CAV Judgment dated 12.02.2021).

Names of Advocates and who they appeared for

- Mr. Ajay Kumar Thakur, Advocate — for the appellant

- Mr. Sanjay Kumar Sharma, Advocate — for the appellant

- Mr. Shyed Ashfaque Ahmad, APP — for the State (respondent)

Link to Judgment

MjQjNzk4IzIwMTcjMSNO-cRPGRBDjVio=

If you found this explanation helpful and wish to stay informed about how legal developments may affect your rights in Bihar, you may consider following Samvida Law Associates for more updates.