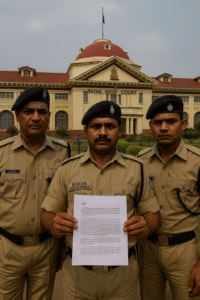

The Patna High Court has delivered an important judgment concerning the removal and transportation of excavated stone materials after expiry of a mining lease in Nawada district. The petitioner—an infrastructure company engaged in national and state highway projects—approached the Court seeking permission to remove broken stone chips and other aggregates lying on two leased blocks (Block Nos. 3 and 6) after the lease period had ended. The company also sought issuance of e-challans and all necessary permissions to transport the material for the timely completion of a national highway project.

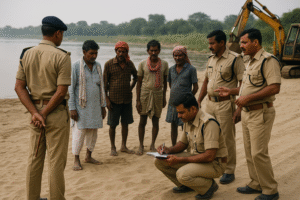

According to the record, the lease for one block expired on 30.12.2020. On 02.06.2021, the Assistant Director, District Mines Office, Nawada, inspected the site and found 13,45,400 CFT of broken stone lying on the mining site. By Memo No. 900 dated 02.06.2021, the company was allowed time from 04.06.2021 to 03.12.2021 to remove broken stone chips, machines and materials. A joint inspection thereafter on 10.08.2021 recorded that 13,12,960.99 CFT remained at site.

While the Collector, Nawada, by Letter No. 1373 dated 17.08.2021, permitted removal of all machinery and broken stone chips/boulders from 20.08.2021 to 19.02.2022, a subsequent Letter No. 1420 dated 31.08.2021 curtailed this permission to machinery/infrastructure only and did not allow removal of broken chips/boulders. Later, the Director, Mines, by Letter No. 2801/M dated 15.09.2021, directed forfeiture of property left on the mining site for more than six months after determination of lease.

In Court, the State expressed concern that allowing removal of the entire stock could jeopardize the State’s interest in GST collection. The State pointed out that the petitioner is registered under the CGST Act, 2017, and urged safeguards to ensure tax realization even though the lease had ended. The petitioner, in turn, argued that royalty already paid covers its liability and sought condonation of delays attributable to COVID-19 restrictions.

The Court (Hon’ble Mr. Justice Purnendu Singh) examined the statutory framework under the Bihar Minor Mineral Concession Rules, 1972, reproducing Rules 9(1)(a), 20, and 21(4). It held that the authority to grant or renew mining leases vests in the Collector; neither the Director nor the Assistant Director has jurisdiction to interfere with issuing or renewing a licence. The Court viewed the abrupt shift from permitting removal (including broken chips) to prohibiting it—without reasons and before the earlier extended period’s expiry—as arbitrary and colourable exercise of power that delayed road construction and caused loss to the contracting company.

On GST/royalty, the Court noted the broader legal landscape: the debate over whether royalty is a “tax” (India Cement; Kesoram Industries) has been placed before a Nine-Judge Bench in Mineral Area Development Authority v. SAIL; it also recalled general GST principles that levy is on “supply” of goods/services under Section 7 of the CGST Act and that assignment of mineral rights may amount to a taxable supply unless excluded or exempted. Still, the Court clarified that the State’s immediate concern was not to re-litigate the nature of royalty but to ensure there is no loss of GST on materials lifted.

Ultimately, the Court directed the authorities to allow the company to lift the entire quantity of broken stone material for both blocks, as quantified by the Joint Inspection Team, within two months. If fresh determination is needed, it must be completed within one week in presence of the petitioner’s representative. Crucially, the Court made it clear that the petitioner must ensure payment of royalty and GST, if any due, within the same two-month window, while the Mines and State Tax authorities have been advised to be vigilant in future so that materials are not removed without realizing statutory dues.

This decision thus balances two imperatives: preventing arbitrary administrative action that stalls public infrastructure, and protecting revenue interests by anchoring material removal to timely payment of lawful dues.

Significance or Implication of the Judgment

This ruling is significant for infrastructure, mining lessees, and government departments in Bihar:

- It affirms that once excavated material is properly accounted for, authorities cannot arbitrarily deny removal, particularly where construction of public roads is affected. The Court expressly found the abrupt prohibition—despite earlier permission and without reason—suggestive of mala fides, and intervened to prevent loss and delay to a national highway project.

- It clarifies administrative roles: under the Bihar Minor Mineral Concession Rules, 1972, the Collector is the key statutory authority for granting/renewing leases and imposing conditions; higher-ranking departmental officers (Director/Assistant Director) cannot override this scheme without statutory backing. This curbs jurisdictional overreach.

- On taxation, the Court does not decide the constitutional character of royalty but gives practical guidance: removal must proceed, subject to the petitioner ensuring payment of royalty and any GST due within the directed period, and with inter-departmental coordination (Mines and State Tax) for data sharing and enforcement. This protects revenue while avoiding project paralysis.

- The direction to complete any fresh quantity verification within one week introduces a predictable timeline for dispute resolution in similar cases, reducing uncertainty for lessees and project authorities.

Legal Issue(s) Decided and the Court’s Decision with reasoning

- Whether authorities could prohibit removal of broken stone chips already quantified after lease expiry, despite prior permission and without recorded reasons.

Decision: No. The Court found the abrupt prohibition, within the period earlier granted by the Collector, to be arbitrary and colourable exercise of power. The company must be allowed to lift the entire quantified stock within two months. Reasoning: Statutory scheme vests power with the Collector; actions lacking jurisdiction/reasons are vulnerable to judicial review under Article 226. - Whether interferences by Director/Assistant Director could override the Collector’s permissions.

Decision: No. Rules 9(1)(a), 20, and 21(4) make the Collector the focal authority; neither Director nor Assistant Director can usurp that role. Reasoning: The Rules themselves; Court’s reading that rights “vest exclusively in the Collector.” - Safeguards for State revenue (royalty/GST) when permitting removal post-lease.

Decision: Removal allowed, subject to petitioner ensuring payment of royalty and GST, if any due, within two months; Mines and State Tax departments to coordinate and remain vigilant. Reasoning: Aligns with GST’s levy on supply; addresses State’s expressed concern; avoids loss to the exchequer. - Timelines for fresh determination of quantities (if needed).

Decision: Any fresh determination to be completed within one week in presence of the petitioner’s representative. Reasoning: Ensures fairness and expedition.

Judgments Referred by Parties

- India Cement Ltd. v. State of Tamil Nadu, 1990 AIR 85 (7-Judge Bench) — discussed in context of whether royalty is a tax.

- State of West Bengal v. Kesoram Industries Ltd., AIR 2005 SC 1646 (5-Judge Bench) — differing view on royalty as tax; matter now before Nine-Judge Bench in MADA v. SAIL.

- Bharat Sanchar Nigam Ltd. v. Union of India, (2006) 3 SCC 1 — GST/VAT context on the nature of supply; read with Gannon Dunkerley v. State of Rajasthan, (1993) 1 SCC 364.

Judgments Relied Upon or Cited by Court

- State of U.P. v. Mohd. Nooh, 1958 SC 86 — judicial review where acts are without jurisdiction or abuse of power.

- Pratap Singh v. State of Punjab, AIR 1964 SC 72; Fasih Chaudhary v. D.G. Doordarshan, 1989 (1) SCC 189 — interference in cases of misuse of power.

- E.P. Royappa v. State of Tamil Nadu, AIR 1974 SC 555; R.D. Shetty v. International Airport Authority, 1979 (3) SCC 489; Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India, 1978 (1) SCC 248; Ajay Hasia v. Khalid Mujib, 1981 (1) SCC 722; Shri Sitaram Sugar Co. Ltd. v. Union of India, 1990 (3) SCC 223 — arbitrary State action violates Article 14.

- State of NCT of Delhi v. Sanjeev @ Bittoo, 2005 (5) SCC 181 — decision-making illegality/irrationality justifies judicial review; power exercised on non-consideration of relevant factors stands vitiated.

Case Title

M/s B.S.C.P.L Infrastructure Ltd v. State of Bihar & Ors. (Mines & Geology Department)

Case Number

CWJC No. 12414 of 2023

Coram and Names of Judges

Hon’ble Mr. Justice Purnendu Singh

Names of Advocates and who they appeared for

- For the petitioner: Mr. Umesh Prasad Singh, Sr. Advocate.

- For the Mines Department: Mr. Naresh Dikshit, Advocate; Mr. Utrav Anand, Advocate; Mr. Brij Bihari Tiwary, Advocate.

- For the State: Mr. Vikash Kumar, SC-11; Mr. Gyan Prakash Ojha, GA-7.

Link to Judgment

MTUjMTI0MTQjMjAyMyMxI04=-tRKCxccgse4=

If you found this explanation helpful and wish to stay informed about how legal developments may affect your rights in Bihar, you may consider following Samvida Law Associates for more updates.